I pored over Charlie Squire’s Slouching in a bus and on a screen — second-choice versions of some of my first-choice activities, riding the train and reading. Squire’s book was born out of a summer spent traveling across Europe — often by train, and occasionally by bus. So while I passed through Albany, I tried to turn the author’s sapid descriptions into my surroundings, imagining the city’s murky river as the Rhone and its decidedly unromantic industrial architecture as Versailles.

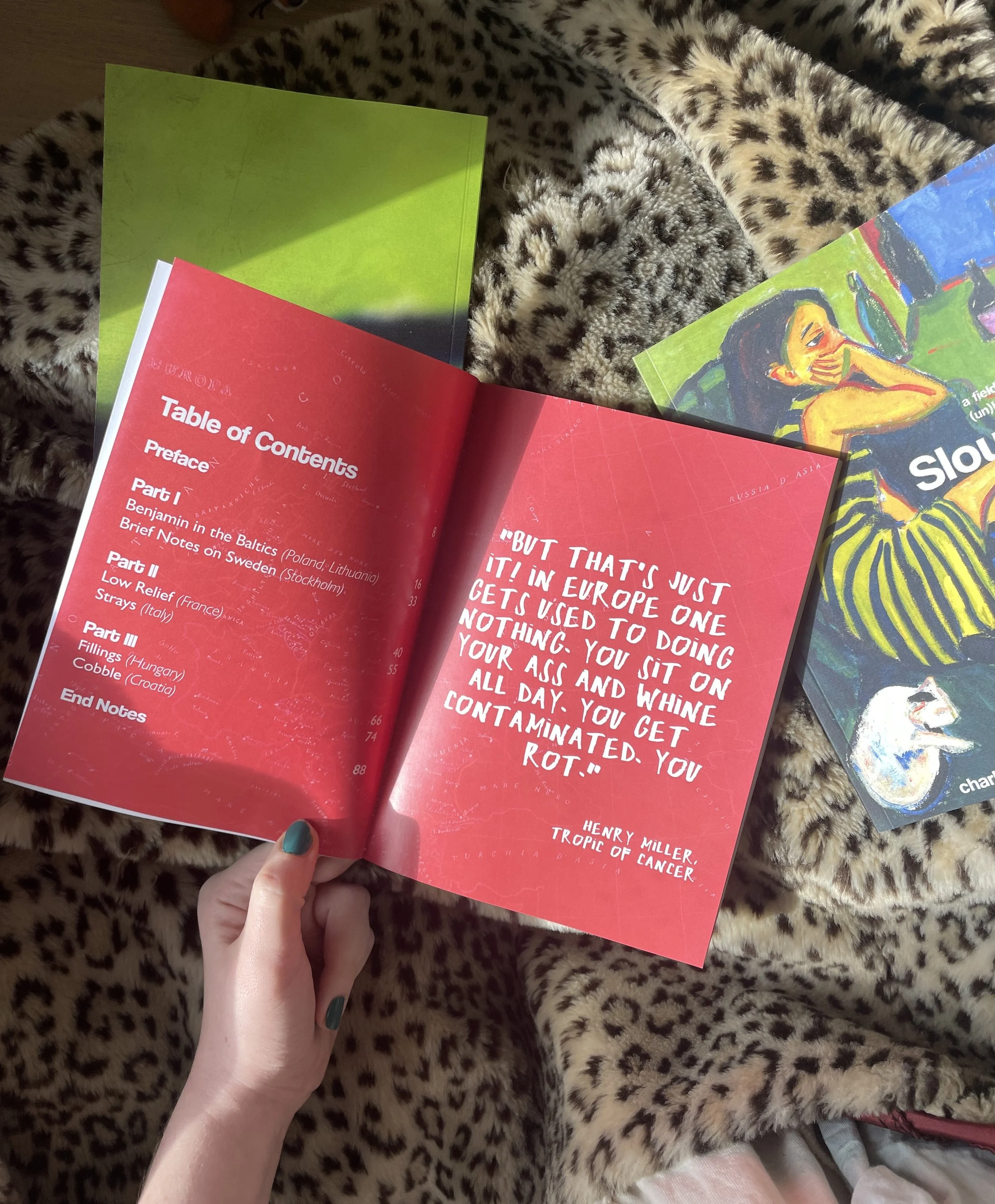

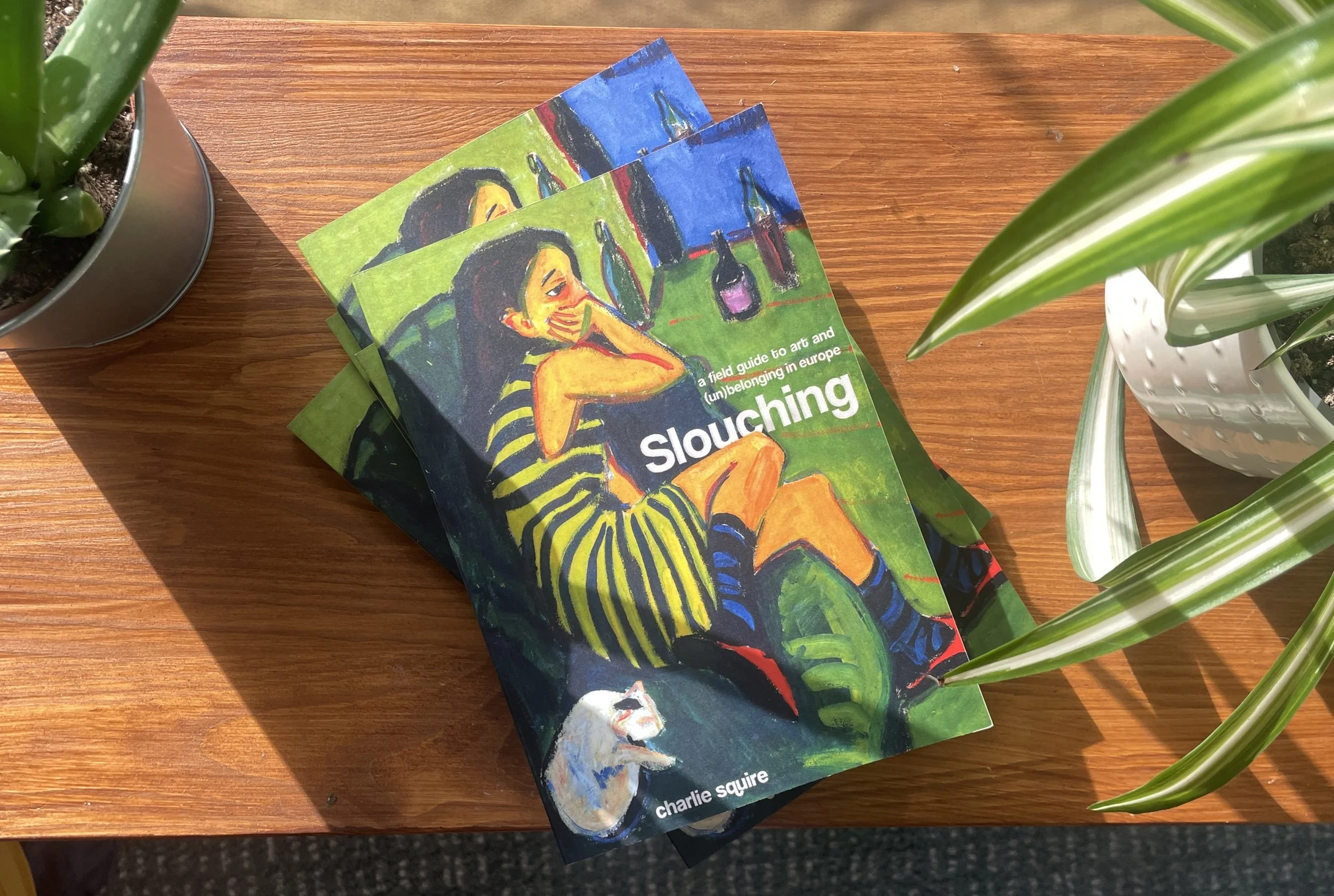

Slouching: A Field Guide To Art and (Un-)Belonging in Europe begins with a painting, a quote, and a confession. On its cover is a technicolored image of a girl — apt to be found (without attribution) on Pinterest boards, but here credited to the German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Its table of contents is paired with a quippy, Euro-critical quote assigned to Henry Miller, the American writer who penned Tropic of Cancer.

Image provided by Charlie Squire.

Several pages in, readers are introduced to Squire’s unmistakable authorial voice in the book’s preface. After imagining all of the marvelous (“had a torrid affair with a pair of married Trotskyist philosophy professors”) and mundane (“gotten a bad sunburn”) tales that might have made for a compelling memoir, they concede, somewhat bashfully, “I took it all seriously.” The chapters that follow reveal just what “it all” is.

The droll self-awareness of Slouching’s preface is characteristic of Squire’s writing. Their prose is most readily found on the blogging platform Substack under the moniker Evil Female, where several of Slouching’s essays first appeared. Evil Female has put Squire in the company of other underground internet royalty and Substack contributors like Rayne Fisher-Quann and Eliza McLamb.

Though the author’s online presence is well-documented, Slouching is Squire’s first major print publication. But then again, as Squire pointed out to me during our call, real life and the internet aren’t so different. For the author, “The internet is as much a part of real life as the streets in front of me.”

Slouching is a collection of personal essays, anthropological observations, illustrations, and collages of found objects. Squire, who graduated from Skidmore in 2021, was one of forty recipients of the Creative Research Impact Centre Europe Fellowship (CIRCE), which awards young academics and budding scientists funding to complete a creative project. Every participant must be under the age of thirty-five. In last year’s cohort, Squire was not only the youngest member, but the group’s lone American.

Funding from CIRCE enabled Squire to spend the summer of 2023 writing, walking, and drinking wine — among other things. Their project purported to tackle the grand concept of geography, considering how spaces facilitate our interaction with them, and in turn, how humans leave evidence of their interaction — whether that landscape is urban or rural, literal or digital. Squire’s itinerary included several capital cities as well as a handful of lesser-Instagrammed towns and pastoral destinations across Europe.

Towards the end of November, the author made time to speak with The Skidmore News about Slouching. We met on Zoom, with Squire phoning in from Berlin, Germany, where they’ve settled since graduating from Goldsmiths, University of London with a master’s degree in cultural and critical theory. We chatted about talking to strangers, compulsive collecting, the qualities of a perfect notebook, and entrusting our writing to others.

Squire readily admits that travel writing — by Americans, in Europe, especially — is well-trodden literary territory. Rather than centering their own American-ness, Squire told me, Slouching speaks unabashedly from the I and attempts to reconcile individual knowledge and emotions. Squire’s undergraduate study of history and graduate concentration on culture and criticism is evident in their approach to the time-worn subject.

Slouching is similarly anchored by a preoccupation with home, often activated by water. Squire is apt to call upon their home state of Maine to conjure up images of rocky coastline and invoke salty, sea-tinted gusts of wind. All of these thematic through-lines have a grounding effect in Slouching, despite its pan-European nature, world-roaming prose, and overall place-ness.

Most of all, memory — collective, national, or Squire’s own — is the central thread that runs throughout Slouching. In each respective city and country, Squire analyzes the museums and monuments that teach, retell, and in some cases, advance not-entirely-accurate narratives about the past. The author maps an emotional landscape, using their own experience and observations to eloquently link past and present. Squire’s skepticism is never snobby, and their passages of judgment are always justified.

Squire told me that “the grounding principle that I was writing from was that physical spaces have the power to affect emotions.” Moreover, they said, “the properties of those physical spaces are consciously designed” and our resulting feelings are by no means neutral — “They’re responses to things that are constructed and constructed by people with ideas and goals.”

As Squire went on to say, “I was aware that whatever observations I had — even the most objective and the most analytical — were things I was drawn to because they were of interest to you me.” Each essay is, in essence, a magnifying glass and the book is filtered through Squire’s own experience and positionality. But their lens isn’t rose-colored nor stained-glass-paneled — it’s sweaty and unvarnished and oh-so-honest.

Image provided by Charlie Squire.

For those of us that still rue the loss of Tavi Gevinson’s brainchild, Slouching is a former Rookie Mag reader’s requited dream. The book has all the hallmarks of a Rookie piece: it seamlessly mingles word and image, muddles the distinction between online and IRL, and puts private reflections on unabashed public display.

In true Tavi fashion, Slouching also includes several spreads of film photography, ticket stubs, pasted-in postcards, and postage stamps. The pages are like a game of adult iSpy, scattered with strips of film and shots of strangers. Squire told me, without a hint of self-consciousness, “I love stuff.” Besides traveling and writing, much of Squire’s research process required gathering analog objects, even — or perhaps especially — the easily-discarded and oft-overlooked.

Sometimes, pairing word and image was a matter of function — “what will look best on the page and what continues the flow of the narrative,” Squire described. More often, though, those decisions were driven by tone. Squire described choosing from a massive envelope of ephemera, selecting only what imagery would most effectively capture the atmosphere. Even something as quotidian as transit cards, Squire said, were worth holding onto “because they felt so specific to the places they were from.” By embedding them in the pages of Slouching, the author went on, “I really wanted to honor that.”

As Squire described during our call, there exists an idea in academia that “our writing about things is in any way separate from who we are as people.” Slouching scoffs at that disjunction, stubbornly wedding head and heart.

This matrimony is perhaps best evidenced by “Cobble,” Slouching’s final chapter and most personal piece of prose. The bulk of the essay elapses over the course of an afternoon in Zadar, Croatia, where the author wallowed, wandered ancient streets, rued, and reflected on the impending end of their fellowship. The essay is emblematic of Squire’s authorial voice — witty, expressive, and epigrammatic without being overwhelmingly ostentatious. “I feel too old for my idealism and too young for my cynicism, which take turns ruling my diary entries and cocktail conversations with predictable irregularity,” Squire writes. “Cobble,” like so much of Squire’s work, is observant, training a discerning eye on its surroundings and, equally, looking inward.

The first-person-ness and personality of Squire’s writing bears a keen resemblance to a private journal. Insightful and intimate, the book is an invitation to peek over Squire’s shoulder. Reading Slouching feels deliciously, guiltlessly, like eavesdropping — another of my favorite activities.

Slouching is available for purchase online. You can sign up to be notified when the book restocks here.