What does one get when two visual artists sit down together? One masterful and passionate look inside making art. Eamon Witherspoon ‘22 spoke to Matthew Neporent ‘20 about his process and inspiration, and the result is a must read.

Eamon Witherspoon: What are you doing right now?

Matthew Neporent: I’m playing around with melting these metals down without any extra sauder. I’m trying to get these strips to adhere onto a greater piece without the metal bubbling up, so it looks as though it’s one piece. I read about this type of fusing and wanted to see if I could do it; it’s not for a project or anything. It’s supposed to be simple, but doesn’t seem to be working. I’m not sure if I didn’t clean the metal enough or something, but it definitely does not look like it does in the book.

EW: It never does. When I tried to cut skateboard decks, I would picture how I wanted the end product to look, but it never turned out that way.

MN: I used to cut decks here last year.

EW: Really? Do you have a press?

MN: I mean, I made really, really janky [boards]. I tried making two nine inch boards with super heavy concaves — I literally just clamped them with seven veneers glued in between for 48 hours. When I came back, the board barely had any concave, but it was a skateboard. It’s like a popsicle.

EW: My friend at University of Vermont is taking a longboard making class.

MN: That is such a UVM thing.

EW: I know, but it sounds so sick. He makes these boards and just puts crazy designs on them. Anyway, why do you enjoy working with metals specifically? And how is it different from sculpture, if it even is.

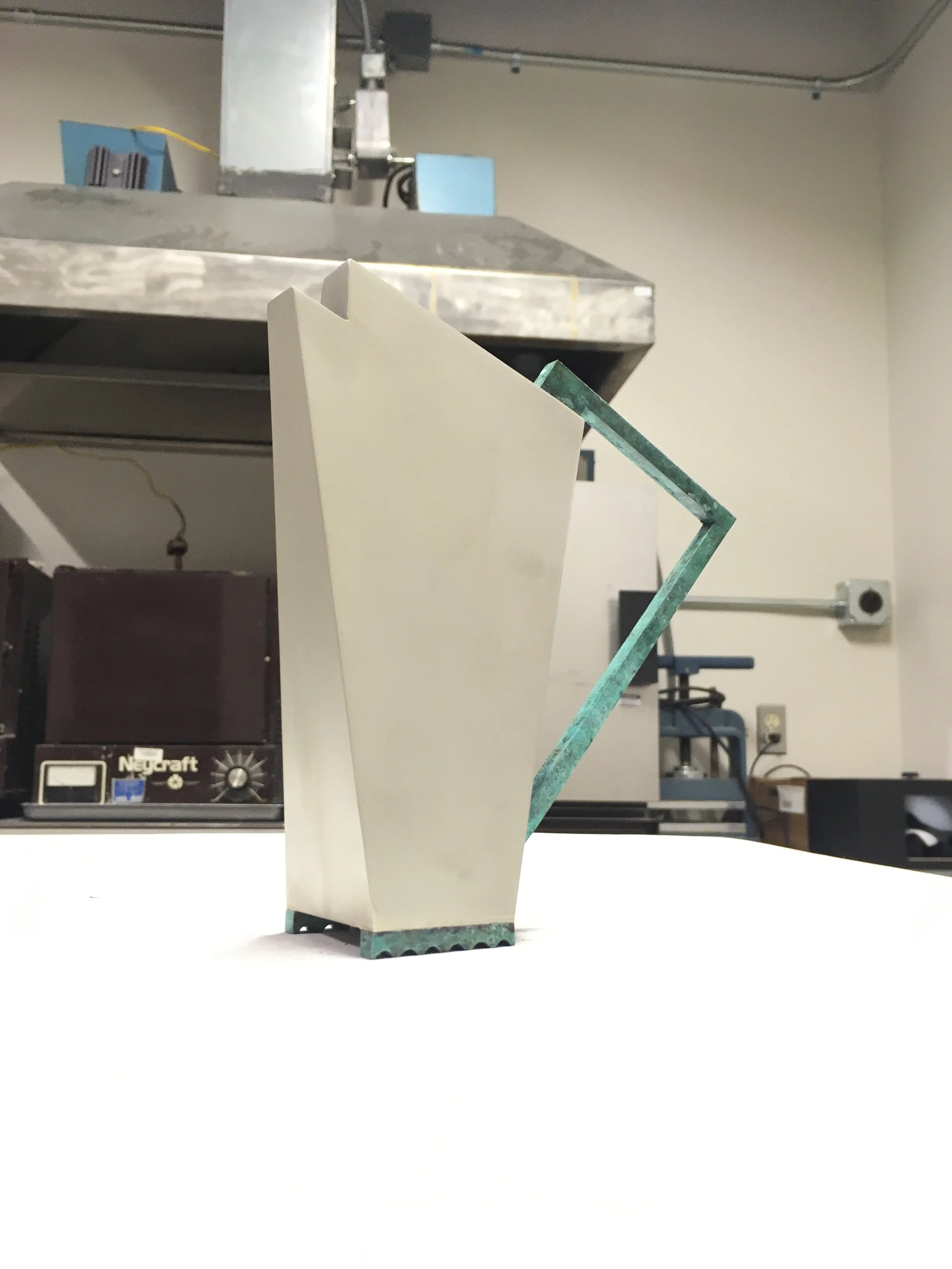

MN: At Skidmore, there can be a difference. Here we work with precious metals and sterling silver and there’s a level of mystery to it. When you can make something other people can look at it but not understand how it was made, which is kind of my main driving factor to do metalwork. There’s an allure to it. If you look at any of these pieces — these are all of my professors work — they’re insane. You can’t really imagine that a human being created these.

EW: Yeah, and from scrap. Well, are they created from scrap?

MN: Mostly. There are some cast elements in them, but most are fabricated. Which is —

EW: Yeah, crazy. What’s your inspiration?

MN: Can I say my professor here? Cause he’s easily my biggest inspiration.

EW: What’s his name?

MN: David Peterson. He is easily the biggest inspiration, he makes the coolest stuff on the planet. This is all his stuff for us to marvel at.

EW: For you, when you create a piece, what’s your mindset going into it? A lot of my creative process when I start out is not having an end in mind. I start out with one idea in mind, and every step influences the next.

MN: That’s the only way you can work in metal. Even if you make a perfect drawing and you do everything according to plan, your piece will never look how you think it will. Somewhere along the way you adjust to what happened and make decisions about what is in front of you, rather than what you want it to be. I guess there are very few times, maybe when you are working on a commision, where you have to make exactly what you planned out. But most of the process is just problem-solving. It’s a lot of “I did this, it looks wack, I’m going to cut it off.”

EW: More of how do I fix it?

MN: Kind of. But that differs because I do a lot of sculpture that isn’t metalwork. Right now I’m making a five and a half foot figurative sculpture that’s stacked from slices; there’s 350 slices stacked on top of each other to build the form. Something like that, my final product looks extremely close to what the original sketch was. But that’s a different type of work. I enjoy that because it’s a bit more methodical and I know exactly what I have to do, rather than coming in for metalwork and leaving behind where I started.

EW: Less thinking involved.

MN: Yeah, more just tedious tasks. Continuing to do these small things that will eventually lead to a large finished piece. But with metalworking, every decision you make affects the outcome. For example [lifting up two small objects] I went a little bit too far trying to finish these. The stem of this one is quite thinner than the other. That represents a decision I’m going to have to make at some point. Are they going to look the same? Or are they going to be two products of a handmade thing?

Photos provided by the artist.

EW: Are they going to be earrings?

MN: They are, they are currently earrings. They’re for my mother. But do you see what I mean? That one is quite a bit thinner than this just because of one decision to roll it a little thinner, and then all of a sudden you’re left with a different result.

EW: I like it like that.

MN: I hope she likes them.

EW: She will, she will. My mom would definitely like these.

MN: Yeah, they’re very mom.

EW: Just the fact that you made them. Your mom will be so stoked. How do you decide what you want to make?

MN: I think a really important thing is I make objects I want; I make things that I want to see and hold. That’s the only reason I spend 12 hours in here a day because I need it.

EW: You spend 12 hours in here?

MN: Yeah, my entire day. I got to the studio today at ten in the morning, and am still here.

EW: Do you have other classes?

MN: I work in the sculpture department so I work there for a few hours before class. I work a little bit more, work in here. I do figure drawing and sculpture, metalsmithing, and the artist interview, where we learn how to interview artists.

EW: Oh, that’s funny.

MN: Yeah.

EW: How would you say sculpture differs from metalwork?

MN: Metalwork is about the process; there’s not a lot of emotion behind the actual work itself. There’s emotion in it, because sometimes you mess things up and are aggravated, but the work itself isn’t often fueled by emotion.

EW: You’re not necessarily trying to portray something.

MN: Right. But in sculpture I definitely am. The things that I make are, I like to think, informed. They come from someone somewhere down the line who made something I liked. The figurative sculptures I make are all in weird, existential figurative poses. They are either in a transition of falling — their arms and legs in the air, toppling over — and that’s a theme in my figurative sculpture and figurative drawing. I tend to make a lot of stuff that is dystopic and existential.

EW: Do you have a reason for making work like that?

MN: Again, it’s just what I want to see.

EW: Why do you want to see that?

MN: I think certain poses speak a lot to me. I also don’t like making things with faces or gender, I like just using the form of the human body and putting it in specific poses. I think more comes out that way. It’s hard to explain; even in critiques no one asks me questions like this. They’ll say “I like the form, it looks good” and I don’t think about it too much.

EW: It just has meaning for yourself, but it’s hard to vocalize

MN: Yeah. I think it probably comes from the sculptors that I look at and find interesting. I worked at a browns casting foundry this summer. The place is not just figurative sculptures, though they are one of the premier places for figurative sculpture on the east coast. They kind of act like a bottleneck for artists around the world who are making large metalwork pieces that need to be cast. They all funnel through the business.

Some of the pieces that I saw there that were in metal and larger than life. And when I saw them in those poses, it stopped me in my tracks. I can’t help but stare at it in awe and wonder all of these things, coming to my own conclusions as to why that form is in that position. Is it a moment of distress? Or comfort? Are they at rest? What’s happening? So much can be evoked from metalwork. I just want to make things that make people think about stuff.

Photo taken from artist’s Instagram.

EW: I guess if you remove the face, you are given less answers to your questions.

MN: I think that’s important — to not put it right in front of the viewer’s face. I think a lot about how art is having to look at something over and over again, continuing to come to different conclusions. When you look at something and understand it, you’re not going to want to look at it again. It’s not going to keep pulling you in.

I think that’s the same reason why people buy some paintings over others. It’s because they see it and they see something that pulls them in over and over again. That idea is hard to articulate when it’s transferred into sculpture because it’s just less obvious what that is. With painting, there’s emotion; the painter has been put on the page. But with the sculptor it’s harder, especially with a figurative form.

EW: What about creativity? How do you stay creative?

MN: Constantly working on different things, even if you have no idea. Right now, I have no clue what my project will be or if I will ever do something with it. But just the thought that it’s possible, that I can fuse two different metals together — two differently colored metals — with different molecular makeups into one sheet to create a pattern and then, essentially, use that to make anything. If you pattern it first,

EW: One thing that I noticed when I do drawings is that I love how it feels in my hand.

MN: Being dirty?

EW: Yeah, I love my hands getting dirty when I draw. It feels really good to have something in my hands and feel the material. Not exactly one with the painting, but having what you draw reflect back onto you. Do you experience that at another level when working with metal?

MN: Your hands get beat up. I finally just got the Gorilla Glue that’s been on my hands for the past five days off. My hands were coated. I was gluing pieces together for my sculpture this past weekend and it literally took until today to come off. I didn't like that at all. That was terrible. I was helpless. There was a film of glue over the pads of my skin, I couldn’t feel my skin. I looked gnarly too. It was all over and black from mixing metalwork and dust. They were disgusting. Gorilla Glue is the worst substance. No, actually, Vaseline is the worst substance. Put that in the interview.

EW: Vaseline? Why?

MN: It sticks to everything and gets off nothing. It’s coated on all our stakes in that room for raising metal.

EW: What is raising metal?

MN: It’s a really slow process, raising metal. In order to do it, you hold it on a metal stake and you have to hit every single spot on the metal. As you do so, the metal grows. As you score the lines, then you can begin forming curves. It’s kind of like a puzzle. What you want to do towards the end is put really methodic hammer marks into it to create a pattern. I could make each piece really smooth, but why would I do that? Why would I create something if not to show that I made it?

EW: I bet you get through a lot of albums with all that time. What do you listen to while you work?”

MN: A lot of different stuff. Sometimes it’s podcasts, you get sick of music really fast when you’re in here.

EW: I’ve noticed that with drawing. When you get frustrated, the music just exasperates that.”

MN: I listen to a lot of Joe Rogan podcasts; sometimes the people on his show are really interesting and then three hours goes by like nothing. When you’re listening to people, I don’t know why, but time seems to go by faster. When you listen to music, you notice every song changes a couple minutes.

“My cubicle.” Taken from artist’s Instagram.

EW: You develop a gauge for it. Moving on, what is your advice for students interested in metalwork, but who don’t necessarily want to take a class, can’t fit the class into their schedule or don’t want to take drawing.

MN: My advice is to take it anyway. I would really recommend it. If metalworking interests you at all — as far as undergraduate metalsmithing studios go, we have one of the best facilities I would say.

EW: I feel like most schools don’t even have metalworking as part of the art department.

MN: We just have such a wonderful professor who is here every single day and really cares. The guy would teach for free if it came down to it. He’s told me that. There’s was low enrollment for the class this semester and we were worried that Dean of Students was going to axe the class. The introduction course will always stick around; it’s the advanced course that is troubling. A ton of people take the introduction course, but only four to five people move forward. Metalwork is a very time consuming thing. And there’s also no faking it. There’s no way to get around that. You either did a good job, or didn’t put the time into it.