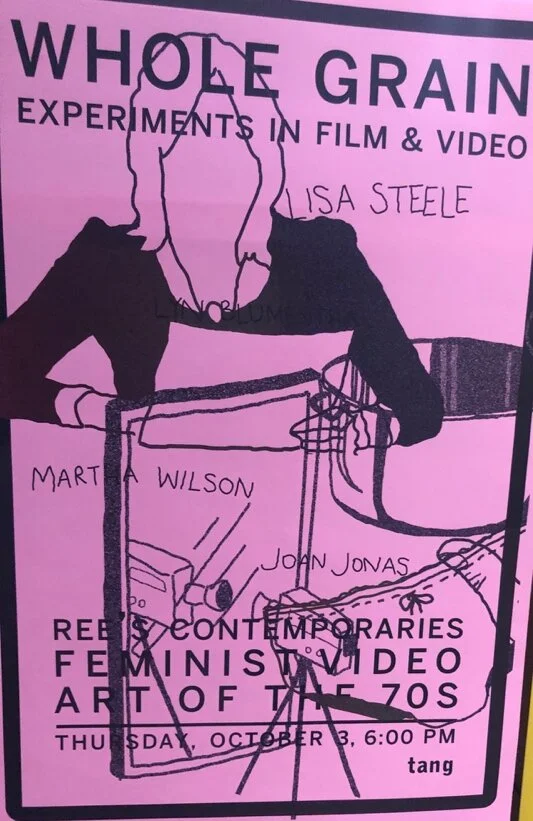

The short films and home videos shown last Thursday at the Tang’s Whole Grain screening of 1970s feminist video art were nothing short of experimental. The female artists who created these films held nothing back — there was nudity, violence, profanity, and absolutely no shame.

Ree Morton, the whole reason this screening exists, is a fascinating Skidmore dropout whose work is currently on display in the Tang. Although Morton never produced any video artwork, there was a surge in experimental feminist filmmaking happening at the time of her most active creative years.

The screening features a 1974 interview with Ree Morton at the height of her career. In the video she discusses her life before art as an unfinished nursing school student at Skidmore in the 1950s. She dropped out of school to get married, and never finished her medical education. Instead, in later years she began to fill her time with art classes at museums, seeing it as more of a hobby than a career path.

However, through sculpture and experiments with form, she began to fall in love with making art. This interview centers around her creative process and focuses a lot on her 1974 exhibit in the Whitney Museum in New York City. Some of the artwork from the exhibit is now at the Tang, in the exhibit titled “Ree Morton: The Plant That Heals May Also Poison.”

Morton’s artwork is personal and public at the same time, addressing issues of the body and nature, but she encourages her observers to interpret her art in any way they please; she feels that there is no wrong understanding of her work.

Every film shown has been shot using an unmistakable female gaze, vastly different from a traditional male gaze found in movies. Though the content of these videos varies greatly, there are aesthetic and thematic similarities throughout. The women who appeared onscreen were almost always the ones operating the camera(s), and they told their own stories.

“Premiere,” a two-minute short film by artist and scholar Martha Wilson in 1972, opened on a centered, unmoving shot of Wilson sitting at a table reading a script. She speaks directly to the audience about presence and performance, about how we are all performing each day in front of metaphorical video monitors.

No less strange was the film that followed: Lisa Steele’s 13-minute, 1974 documentation of “Birthday Suit with scars and defects.” She stands before the camera, on her birthday, in her birthday suit, explaining in excruciating detail the stories of each scar and blemish that appears on her skin. It is an unapologetic expression of admiration for her womanhood.

Two films by Cynthia Maughan, both just a minute long, document a close up of one particular body part and one action that contradicts societies standards for what that action should be. “Razor Necklace” is simply Maughan putting on a necklace, a sign of femininity, but this necklace is a string of razor blades and is placed carefully and slowly around her neck. “The Way Underpants Really Are” shows a pair of loose, torn, baggy underpants.

“Left Side Right Side” is a trippy experimentation with mirrors and lenses, and performance artist Joan Jonas plays around with perspective and images using a mirror and a monitor in this fascinating 9-minute video. In Lynda Benglis’ “Female Sensibility,” footage of two women kissing and embracing — though the camera is too close to see their entire faces — is accompanied by obnoxious male-narrated college radio programs.

Experimental and at times confusing, these short films are an extremely honest lens with which we have the privilege of viewing a period of rapid social change. These women picked up their own cameras and pointed them at themselves, and through these archives we now have the rare opportunity to see them.