The Other Side: Art, Object, and Self exhibit at the Tang Museum explores and emphasizes contrasting concepts like life and death, seen and unseen, loss and hope, artifice and truth. The exhibition features sculptures, photographs, prints, paintings, and fiber art pieces designed by artists such as Willie Cole, Yinka Shonibare MBE, Jamal Cyrus, Flor Garduño, Tim Hawkinson, Michael Joo, and Miguel Aragón.

The exhibit includes provocative sculptures and paintings alongside deeply emotional pieces that encourage viewers to make critical examinations of their cultural and personal identities. Each of the works depicted below illustrate a powerful and important topic, ranging from issues including race, identity, and basic rights. The exhibit is able to combine all these unique interpretations to create a moving array of emotions and ideas that evoke deeply personal connotations.

Here is each piece seen in the exhibit with a quick summary.

To Get to the Other Side, Willie Cole 2001:

The caricatured black lawn jockey is infamous in reflecting Jim Crow-era racist ideologies. However, Cole tries to reimagine the jockeys into a posture of strength and combat. Furthermore, the figures are equipped with knives, bags, neckties, beads, and other items to reflect their roles on the chessboard as well as reflecting traditional African symbols and items. Each lawn jockey is a stand-in for the Yoruba god “Elegba,” the gatekeeper who represents games and chance.

Untitled (melancholy dame/ carmen jones), Lorna Simpson 2001:

With this arrangement of images, the artist combines portraits of a woman with titles of 20th century films that present black women as highly sexual, erotic commodities. Obscured by vinyl overlay, the subject’s face is never completely revealed, implying that she could be and look like anyone. Without being able to see her, the public is left with only the short phrases surrounding the images, presented together by the artist as an inner monologue with a racist and stereotypical undertone.

Untitled (DRWN), Michael Joo 2012:

Made of graphite and urethane, disembodied African crane legs sit at the base of faint lines drawn directly on the wall. Having a human hand draw the lines refers to both literal and figurative duality, as the more the artwork is shown, the more the lines themselves will wear away. However, the graphite in the legs, a carbon-based compound, remind the viewer that while it may be only temporary, carbon is still the basis of all life.

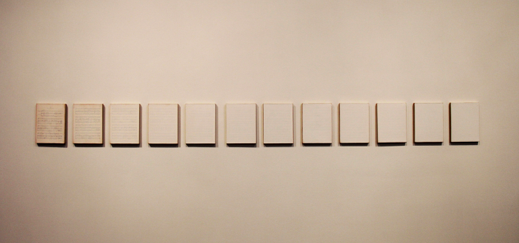

Winterreise (songs XX-XXIV), Tim Rollins and K.O.S. 1988:

This display shows the existential questioning of a wanderer in the song cycle Winterreise. It begins with a transparent or clear form of the song, but then turns into opaque whiteness when the last song is reached.

The song itself tells the story of a beggar playing for nobody but himself. Here the artists try to present a tabular rasa, or a blank slate, but supposed snowfall then covers the song as the end approaches and brings about notions of unavoidable disappearance.

The Fin Within, Tim Hawkinson 1998:

This sculpture represents the space between the sculptor’s legs. An area Hawkinson considers to be a metaphysical and mythological object typically known to contain empty, negative space. The texture on the aluminum alludes to a different species, meant to raise questions about where one species ends and the other begins. Therefore, Hawkinson asks us to consider the space the body creates, rather than the body itself.

Famous Twins, Beverly Semmes 1993:

In the display of the two dresses, Semmes presents the trappings of what is presumed to be female twins. These twins are in the same colors but opposite configurations. Semmes wanted to show how, even though they may look nearly identical in shape, the twins still can be seen as opposites to each other, good and evil.

The beyond-human and abnormal scale of the dresses draws attention to the actual absence of the presence of bodies, displaying the weight that the dresses hold in telling identity.

Constitution on Tour, Kate Ericson and Mel Ziegler 1991:

The display of the trains is a response to a nationwide tour of the Bill of Rights in 1991 sponsored by tobacco giant Philip Morris Co. Each train carries pieces of marble that were not only used to construct the Supreme Court, but also painted with the words of the United States Constitution. By doing so, Ericson and Ziegler try to emphasize the hypocrisy of a tobacco company touring a document that defines basic human rights.

(left to right) Untitled (Threads), Jamal Cyrus 2016. HeVi, Oslo, Zanele Muholi 2016. Carla, Mexico, Flor Garduño 1998:

Cyrus’s canvas resembles sheet music or text with ostensibly confidential sections, referencing state-sanctioned efforts to remove information and potentially alter history.

Zanele Muholi, the subject of her own artwork, nearly disappears into the background, and is only visible by the white in her eyes. The piece is a declaration of her beauty as a black and queer South African woman. Her nude appears blends into nature and dares the public to conjure stereotypes of black women.

While Muholi disguises her nudity, Garduño’s subject displays her body in a gesture of pride and power. She remains in control, delicately veiled by floral imagery — symbols of beauty and femininity. Side by side, Muholi’s and Garduño’s pieces offer two views of the female body that both displaying strength and fragility.

Pharaoh Fetish, Fred Wilson 1993:

Here Wilson uses objects to encourage the reconsideration of social and historical symbols by reframing their conventional interpretations. He emphasizes the “fetish” for Egyptian artifacts by placing a plaster of a pharaoh, a common souvenir in Egypt, and images of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti to allude to the power of Egypt.

Meanwhile, leather cords are used to reference enslaved people, and beaded necklaces and Pan-African colors symbolize the African Black Power movement of the 1970s.