In a time when our country has seen gay marriage become legal in all fifty states and major progressive social reform take hold all over the world, it’s hard to imagine a place where state-sanctioned homophobia exists and being gay is punishable with a lifetime of imprisonment.

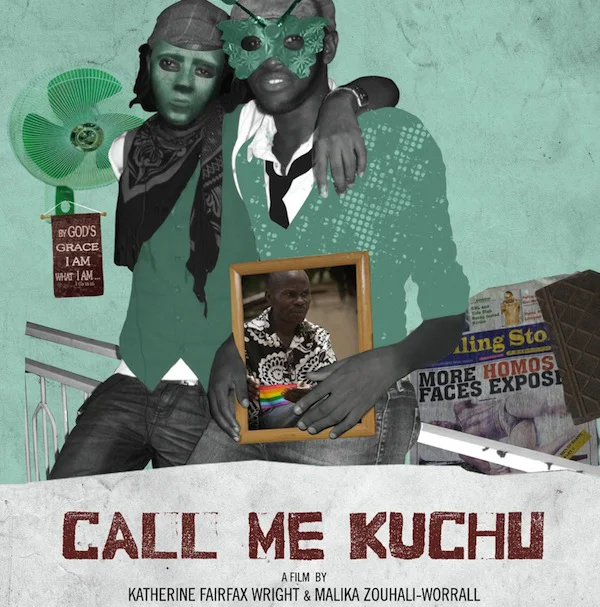

In their documentary, Call Me Kuchu, filmmakers Malika Zouhali-Worrall and Katherine Fairfax Wright explore the dynamics of LGBT activism in Uganda while the Anti-Homosexuality Act, also known as the ‘Kill the Gays’ bill, is trying to be passed.

The documentary was screened in Davis Auditorium on Tuesday, September 29. Only a few people came to watch, but everyone who did was incredibly moved, and loud sniffles could be heard over my own. The film effectively chronicles members of an LGBT community at odds with the law, as well as their entire country, as they struggle to gain their rights as human beings. It follows the lives of David Kato, one of the activists on the forefront of the LGBT movement in Uganda, and his friend Naome, a lesbian activist, along with a few others.

Although most religious leaders in Uganda are very against supporting this issue, Bishop Christopher Senyonjo offers his strength and warmth to the LGBT community, accepting them as people. He helped them set up a safe house and support group for their community. While David and his fellow activists were desperately trying to gain footholds in society and advocate for LGBT rights, risking their lives to do so, a bill condemning homosexuality and proclaiming it as illegal was sent to Parliament.

David then worked with his friends to tackle this issue and repeal the bill. Towards the end of the documentary, the President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, warns the country to be cautious in passing this bill because it could sever ties with western allies and potentially isolate the country. Eventually, the bill expires, a brief victory for the LGBT community, but not for long as a tragedy strikes the LGBT community once again.

One of the co-directors of the film, Malika, discussed the aftermath of the film with me, explaining that she stayed in close contact with the people from Uganda. She talked about how the Anti-Homosexuality bill was re-introduced into Ugandan law and passed a few years after her film was made, but was then withdrawn because it was revealed that the bill had been passed illegally

With her part-British, part-African descent, she is aware of the single narrative that recounts the story of Africa being “poor and backward.” She wanted to use this opportunity to tell a different story of Africa from the perspective of intelligent, socially-conscious Ugandans fighting for freedom.

Although the struggle for LGBT liberty in Uganda is far from over, after the Anti-Homosexuality bill was overturned, Uganda celebrated their first gay pride rally in 2012. “Call Me Kuchu” was chosen out of tons of other films to be screened during the rally. Malika described that moment of recognition as the “biggest sense of validation,” which the film unquestionably deserved.